Embeddings in a nutshell

What are those embeddings you hear about every day? Find out in this article - many buzzwords will cease to be black magic 🧙

Let’s assume we want our computer to process some text.

The application can be anything:

- we ask ChatGPT to proofread our message,

- we try to translate a message,

- or, for example, we use an algorithm to recognize emotions in text.

In all these approaches, one problem arises.

How can a computer, which thinks in numbers, bytes, and bits, process text made up of human speech—words and letters?

Well, before processing begins, the computer translates the text into its own language. It turns words and sentences into a set of numbers with a specific structure, called embeddings :)

What are embeddings?

Embeddings are a representation of text [1] in the form of an N-dimensional vector. The text can be a word, a sentence, several sentences, or even several paragraphs.

For example, the word “Cat” might be turned into a vector [0.123, 0.892, 0.004, ..., 0.572] containing 300 numbers with values between -1 and 1.

The sentence “I really like eating chocolate during winter” would also be turned into a vector with an identical structure - we would get 300 numbers with values between -1 and 1.

The vector values themselves are unreadable to us humans. For instance, we cannot glean any information from the fact that we got -1 at the 54th position of the vector, or 0.5 at the 13th position.

Info

[1] Embeddings can also be generated for images, videos, or audio. The concept of embeddings refers to converting complex data (like text or an image) into a vector of numbers.

To keep the article simple, I will discuss only their textual significance, as it is currently the most widely used :)

What do embeddings give us?

Comparing two vectors allows us to determine how semantically similar the corresponding words/sentences are.

It’s not about the construction of the word itself—whether “current” is similar to “currant”, “curent”, or “currnt”—as is the case in traditional keyword-based search.

Semantic similarity is determined in a human way—do the words/sentences have similar meanings?

Comparing words - a history of embeddings

word2vec

I’ll present an example based on the pioneering word2vec algorithm, published in 2013 by Tomáš Mikolov from Google.

The word2vec algorithm was created by processing a very large corpus of text. This enabled the autonomous discovery of similarities without the need for supervision or additional work by researchers (unsupervised learning).

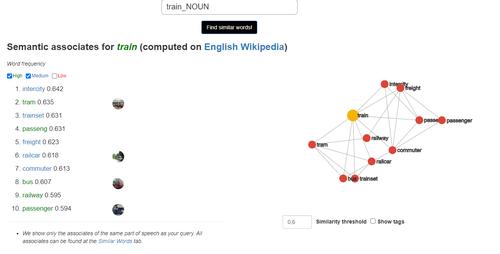

The word “train” is identified as similar to “intercity”, “tram”, “trainset”, “freight”, “railcar”, “passenger”, “bus”:

- “train” - “tram”/“bus”, because public transport;

- “train” - “freight”, because freight rail;

- “train” - “passenger”, because passenger rail; …

Despite the words having completely different constructions, the algorithm accurately captured their meaning by establishing similarities.

Imagine how much this facilitates searching on the Internet! To find results related to “urban transport”, “municipal transport company”, and “timetable”, we just need to type “public transport”. It is no coincidence that leading research (both for word2vec and the later discussed BERT) was conducted by Google.

The mechanism for comparing embeddings is a simple mathematical operation. We measure the distance between two points—only instead of two or three dimensions, as in math class, we operate in N dimensions, where N is the size of the vector.

Key takeaway - comparing existing embeddings is much faster than generating new ones.

Moreover, vectors in word2vec can be manipulated:

If we add a second vector to the first one, and then subtract a third vector, it may turn out that the result is very close to an existing word! [3]

- Result “man” + “queen” - “woman” is closest to “king”

- Result “Rome” + “France” - “Paris” is closest to “Italy”

- Result “Man” + “Sister” - “Woman” is closest to “Brother”

Amazing, isn’t it? :)

Comparing sentences

I presented the examples above for single words, but the algorithm works equally well for sentences or sets of sentences.

Let’s assume we have a knowledge base in the form of the following 3 sentences:

- The holidays are coming!

- Peanut butter is a good source of protein.

- Maciej is wearing a red Christmas sweater…

We also have a question for which we want to find the most similar sentence:

- How to improve my diet?

When we:

- generate embeddings for all 4 sentences

- and compare all 3 pairs (question embedding) - (sentence embedding)

For each pair, we will receive a numerical similarity value - the higher it is, the closer the sentences are.

The most accurate match for the question “How to improve my diet?” will likely turn out to be the sentence “Peanut butter is a good source of protein.” - despite the fact that no keywords overlap!

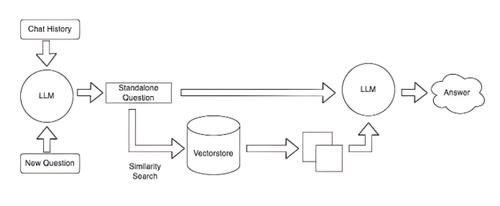

This technique is used, for instance, in Retrieval Augmented Generation, which allows us to find the most relevant documents for a user’s question, and then have an LLM (like ChatGPT) provide an answer based on them.

Newer algorithms

The main problem with word2vec is its poor recognition of context for words. For example, in the sentences:

- apple and banana republic are american brands

- apple and banana are popular fruits

The same embedding will be generated for the words “apple” and “banana”, even though in the first sentence they refer to companies, and in the second to fruits. [12]

word2vec was quickly replaced by newer models generating higher quality embeddings.

It is crucial to compare embeddings obtained using only the same method. Juxtaposing embeddings generated by two different models will not yield any measurable result.

BERT

In 2018, researchers from Google introduced the BERT model, based on the transformer architecture. [5]

Unlike word2vec, in BERT, word embeddings are context-dependent. Moreover, BERT enabled embedding entire sentences! For the sentences below:

- apple and banana republic are american brands

- apple and banana are popular fruits

The different meanings of the same words “apple” and “banana” will no longer negatively affect the quality of the embeddings.

However, due to a different architecture, BERT makes it impossible to operate on embeddings as in the examples above - whether through neighbor visualization or vector math. [12] Fortunately, this is completely unnecessary in practice :)

SBERT

BERT worked great for single words, but embeddings of entire sentences were not yet polished.

In 2019, the SBERT model was created, improving the BERT model and facilitating the comparison of individual sentences. [6]

For each sentence, SBERT generates a vector (an embedding) that we can operate on outside the neural network. The speedup of the process relative to BERT while maintaining quality turned out to be gigantic, because the SoTA solutions of that time required calculating similarity through BERT inference on each sentence pair. SBERT enabled SoTA performance using only generated vectors. Quoting the original paper:

BERT (Devlin et al., 2018) and RoBERTa (Liu et al., 2019) has set a new state-of-the-art performance on sentence-pair regression tasks like semantic textual similarity (STS). However, it requires that both sentences are fed into the network, which causes a massive computational overhead: Finding the most similar pair in a collection of 10,000 sentences requires about 50 million inference computations (~65 hours) with BERT. The construction of BERT makes it unsuitable for semantic similarity search as well as for unsupervised tasks like clustering.

In this publication, we present Sentence-BERT (SBERT), a modification of the pretrained BERT network that use siamese and triplet network structures to derive semantically meaningful sentence embeddings that can be compared using cosine-similarity. This reduces the effort for finding the most similar pair from 65 hours with BERT / RoBERTa to about 5 seconds with SBERT, while maintaining the accuracy from BERT.

Increasing the accuracy of sentence comparison

I’ll return to the topic of comparing sentences for similarity. This is currently probably the most common application of embeddings.

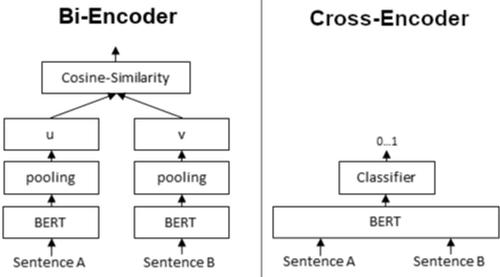

Bi-encoder

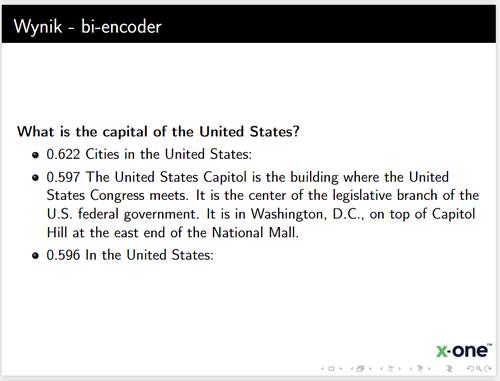

The simplest method is comparing their corresponding embeddings using cosine similarity. This is the so-called bi-encoder. This is exactly the same mechanism I described for the SBERT example :) It is also currently the most commonly used method in GenAI applications - we receive embeddings from an API, save them in a database, and then perform operations on them.

The method is effective and fast, but strictly speaking, it is not the best in terms of quality.

Cross-encoder

Much better quality is offered by the cross-encoder: [13]

- A Bi-encoder returns a vector for a single text fragment, which we can then compare with any other vector.

- A Cross-encoder returns a value between 0 and 1 for two fragments, indicating how close the two words, sentences, or documents are.

However, the problem is speed. Inferencing the model is time consuming, but cross-encoder requires us to calculate each pair of sentences for every single search! We are unable to do that within a reasonable time once we have a sufficient document base (as indicated by the quote from the SBERT paper).

So how do we use a cross-encoder to improve search quality?

Re-ranking

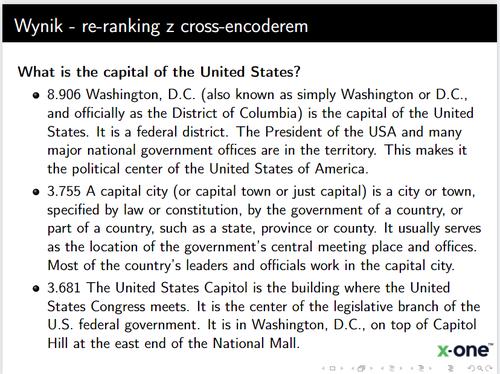

Re-ranking comes to the rescue: a technique that allows us to use a cross-encoder to select the best fragment from a set of candidates chosen by a bi-encoder. [14]

- First, we search for a large set (e.g., 100) of the most relevant texts for our question;

- Then we use a Cross Encoder to examine the similarity between the question and the received texts.

This significantly increases search relevance for a relatively small increase in waiting time for the answer. The increase in quality is very noticeable with large text collections.

You can treat this as a preliminary screening of candidates (high recall), from which we select the best matches (increasing accuracy).

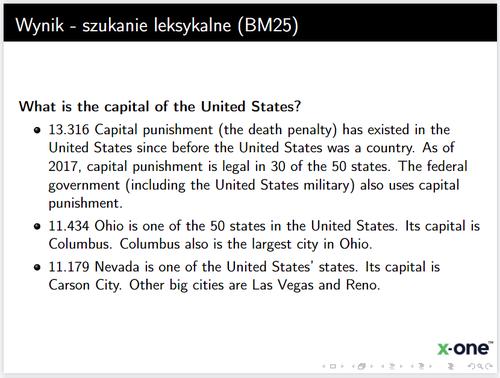

Demonstrating with an example based on data from Wikipedia, using the bi-encoder ‘multi-qa-MiniLM-L6-cos-v1‘, the cross-encoder ‘cross-encoder/ms-marco-MiniLM-L-6-v2‘, and lexical search BM25: [15]

The answers received after re-ranking are significantly better than the answers found by BM25 and the bi-encoder alone:

The fragments after re-ranking refer directly to our question - the technique works :)

Increasing comparison speed

Searching for relevant embeddings becomes time-consuming with large datasets.

The simplest method, iterating through vectors one by one, has linear time complexity relative to the size of our embedding database.

10 million embeddings require comparing 10 million vectors for each search query.

For this reason, vector databases were created to speed up the search process. [16]

It should be mentioned that speeding up the search is a lossy process. We are unable to maintain perfect search quality while reducing the time. However, this is often an acceptable trade-off in production systems.

Efficient vector storage is possible even in Postgres using pgvector. [17]

Example in Python

SBERT is available under the Python library SentenceTransformers. Using it requires just a few lines of code:

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer, util

model = SentenceTransformer('all-MiniLM-L6-v2')

emb1 = model.encode("This is a red cat with a hat.")

emb2 = model.encode("Have you seen my red cat?")

cos_sim = util.cos_sim(emb1, emb2)

print("Similarity: ", cos_sim)

We can generate embeddings using only the CPU. Having a graphics card will speed up this process, but it is not required for model inference (querying).

Which model to use for generating embeddings?

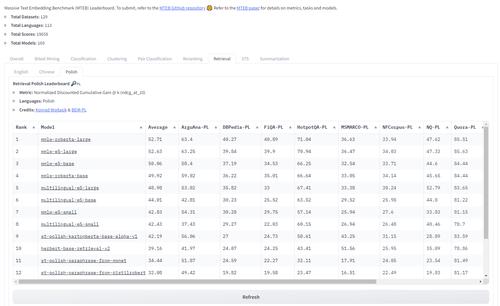

We can choose a model based on the MTEB leaderboard, which presents the quality of individual models for various tasks and languages - including Polish! MTEB stands for Massive Text Embedding Benchmark.

We can filter the ranking by tasks such as classification, reranking, or retrieval.

Using the example of searching for the sentence closest to a question, to find the appropriate model, we should select the “Retrieval” tab and the language you’re using - personally, I would choose Polish ;)

Specialized applications

As a side note: we can fine-tune an embedding model on our own text corpus. Such a solution improves results because the model has a chance to learn specialized vocabulary in the appropriate context.

The company responsible for Kelvin Legal trained their model on a corpus of legal and financial documents, significantly outperforming other models in relevance for related questions. Their smallest model handles legal documents better than OpenAI’s largest model! [11]

That’s all for today. Thanks for reading the article! :)

You can follow my blog with any

Maciej Kaszkowiak

I try to write about interesting things, such as artificial intelligence, created projects, and travel - see all posts.

Query rewriting - refine user queries

What is query rewriting? Why is it useful whenever you build a chatbot? How to implement it? Read the article!

BM25: keyword search

Improve search in your application! Implement BM25: discover how it works, learn about potential issues, and get practical advice 🚀

Even your cat poem generator requires proper tests

Benchmark your AI application. Learn why and how to do that!